Theology on the Back Side

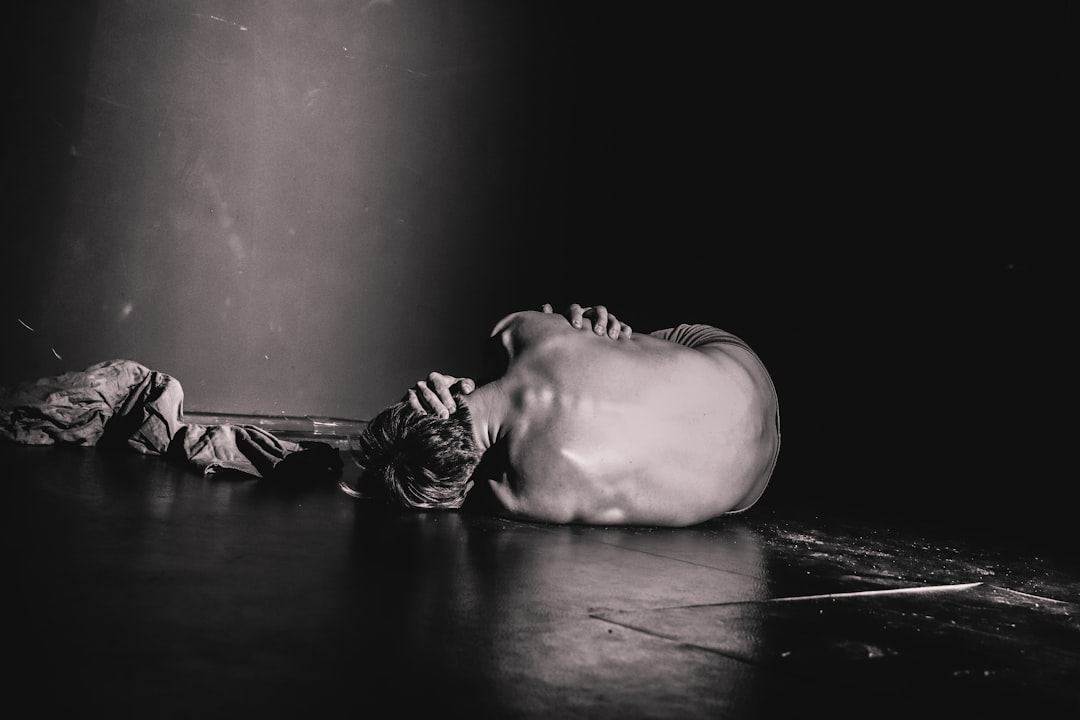

An Improvisation on Wesleyan-Holiness Theology for the Sinned Against

Trigger and Content Warning: This post contains references to abuse, abandonment, and rape.

The Church has primarily focused upon the sinner in wealthy, western countries like the United States. By primarily focusing on the sinner in wealthy, western countries like the United States, the Church discusses soteriological concerns in a certain way and leaves many out of the grand story of God. This focus has shaped language, liturgy, and exegesis. What if the Church worked out a more holistic and balanced theology that sees from the perspectives of the sinned against? Working in a Wesleyan-Holiness improvisational theology with the back side of the cross will have implications for pastoral decisions, ecclesial and communal worship, and soteriological language and concerns. The idea of back side theology must be introduced as a foundation for discussing its implications on pastoral decisions, ecclesial and communal worship, and soteriological language and concerns. From that foundation, an improvisational approach to incorporating back side theology into the pastoral framework to include the work and witness of the pastor through storytelling. Then a move toward how back side theology and the pastoral work inform the ecclesial work of communal worship through liturgy and language. Finally, the implications for our soteriological language, focus, and mission will show how our improvisation builds into a work that reveals a faith rooted in the ancient Church, yet timely for a meta-modern world.

Back side theology is a type of liberation theology. But back side theology differs from standard liberation theology by identifying the need for liberation from the point of view of victims rather than a more narrow, ethnic, racial, geographical, or other context. [1] Back side theology is a call to action in the style of liberation theologies because it demands that we see the sinned against and that there is resurrection hope for the sinned against. [2]Drs. Leclerc and Peterson explain, "All victims need liberation in some way, in the sense of being freed from a disempowering and dehumanizing woundedness, that may be presently happening or that happened years earlier." [3] To view back side theology in the negative would be that back side theology is a rejection of theodicies which defend or excuse God for suffering. As a liberation theology, back side does not seek to answer the question of suffering or evil. Instead, the back side acknowledges that evil and suffering exist and that the victims of evil and suffering need resurrection and a path to wholeness. Back side theology seeks to woo the sinned against into healing through the solidarity of the Jesus event climaxing in the cross, but leaning into the entire Jesus event. As a liberation theology that speaks to all those sinned against, back side theology has hopeful stories to tell those on the back side of the cross.

Pastoral shifts in light of back side theology are many, but for the scope of this essay, storytelling will be how back side theology is incorporated into the pastoral work. Craig Keen has recently argued that the term pastor may not be the best at what the work of the pastor entails. He explains why he sees bishop as a better term, "their task is to watch over the work of these people (their liturgy), and it is this body’s martyrial sacramental work, in the hands of the Son and the Spirit, that makes them a church. And indeed that is what they were called until the hierarchical Roman military provided a template for power wielding accommodating ecclesiasts, who turned 'the bishop' into an administrator."[4] A comment mentioned that "parson" may be a good term as well. Thinking of pastoral ministry as a watching over "martyrial sacramental work" allows us to see the pastor as a storyteller. In back side theology, the storytelling will not look like the revivalism of convicting sinners to repent as Billy Graham or DL Moody.[5] Instead, the story may tap into the ethos of hip hop like Queen Latifah's "U.N.I.T.Y" or Public Enemy's "Fight the Power" (the original and 2020 remix).[6] The latter gives voice to the sinned against and laments the actions of the sinners. Those on the back side of the cross do not hunger for information laced treatises on how to overcome sin, instead, they want to feast on the hope born out of being seen and heard. Once seen, healing is much easier to attain.

While the pastor may bring in the stories and art of culture to illuminate the truth of the sinned against, she may also engage familiar stories of scripture in ways that highlight the sinned against and even turn stories in on themselves to cause the sinner to recognize complicity in harm to the sinned against. Two examples of stories that can be seen from the back side include that of Hagar the slave who births Abraham's firstborn and Bathsheba, who encounters David in a forced sexual encounter. Hagar is used, abused, and ultimately abandoned by Abraham and Sarah (Gen 16-21). Hagar is seen and heard by God. At a moment when Hagar has run away, God speaks to her and speaks promises outside of Abraham's promise. Hagar responds by naming God "El-roi" or "the Good who sees me." (Gen 16:13)[7] The pastor can also tell the story of Bathsheba from the back side of the cross which is a different side to the story of David. An example of how to navigate this story as one of rape by a ruler, the story as told in chapter two of the book Back Side of the Crossis a helpful prompt. This is a view of the story which can resonate with the sinned against as it shines a light on the true sin of David.[8] While it is unhelpful to make the people voyeurs, the unvarnished horror or pain of these stories can invite the sinned against into the story and point the sinner toward the pain of the sinned against. These also help when attempting to understand the ecclesial and liturgical concerns for the sinned against.

Liturgy is "a form or formulary according to which public religious worship, especially Christian worship, is conducted."[9] Liturgy is a worked-out expression of theology, faith, and practice. For those on the back side of the cross, liturgy often obscures their view and obscures them from view. The formal liturgies of higher churches may lean too heavily on visions of God as an all-powerful male distantly judging the sins of the people. The lower evangelical liturgies may be a less formal vision of a distant male God, but the tenor becomes about celebration, happiness, and personal relationship with God. The language of liturgy should work toward being accessible and wooing for as many as possible. To accomplish this, the language of gender neutrality should be an aim of language. Depending on the context, alternating masculine and feminine terminology may be appropriate. Julian of Norwich, writing in the medieval period recognized God held both male and female in her Revelations of Divine Love. "God is Very Father and Very Mother of Nature: and all natures that He hath made to flow out of Him to work His will shall be restored and brought again into Him by the salvation of Mankind through the working of Grace."[10] Regardless of the context, choosing gender neutral language will allow more to imagine themselves in the stories being told and be less likely to view God with potentially trauma inducing words such as mother and father.

Beyond the language of God, the way liturgy is considered and worked out is another opportunity to woo the sinned against. In the sacraments of baptism and communion, the Church can work through the context of the sinned against, besides the sinner. In baptism, belonging and resurrection can be highlighted besides the cleansing metaphors. Baptism as an invitation to join a family not bound by the pain and trauma of biological family may be appropriate. The pledge of the baptized (or their guardians) to reject the world and embrace God can be a positive for the sinned against. The Eucharistic celebration as a receiving of grace can be another invitation to woo. Imaginative language of liturgy that invites the sinned against to take part, an open and welcome table, and subtle change in language can help those on the back side to be seen. An example of changes is the liturgy of the table beginning on page 360 of Back Side of the Cross including the idea that Christ gives himself over willingly in solidarity. The prayer of confession and lament highlights the hope of back side theology:

We confess the ways we have sinned against you and others and pray you will allow us the opportunity to seek their forgiveness in a spirit of repentance and sorrow. We also pray along with those who come to the table and are broken and in pain because of abuse done by others. We here lament for all the ways this world is not as it should be. We pray in solidarity with those seeking healing to replace unspeakable sorrow and unmerited shame. Within our confession of sin, our confession of need, and our expression of lament, we ground our prayer in praise to you who bore our shame and became sin for us on the cross. We also praise you for the gift of hope and new creation afforded to us in his resurrection.[11]

Resolving the improvised solos of pastoral work, the language of liturgy, and the sacramental work informs and brings all together in the soteriological language of the church working on the back side of the cross. Combining the storytelling of pastoral work, the language and care of liturgy, and a sacramental approach, therapeutic and healing metaphors within relationship may become more pronounced in back side theology. Our discussion of the cross must include the totality of the Jesus event from Bethlehem to Ascension. When we speak of the cross, metaphors which speak to the sinned against may help to illuminate the work as for the sinner and sinned against. Metaphors like the lynching tree in James Cone's Cross and the Lynching Tree show us the nature of the innocence of Jesus on the cross, killed by the violence of humanity. "The cross is a paradoxical religious symbol because it inverts the world’s value system with the news that hope comes by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word, that the last shall be first and the first last."[12] The base of back side theology improvising with a pastoral focus on storytelling, intentional shifting of language and liturgy, all informing our soteriological language invites and woos the sinner and the sinned against into a relational community of hope and transformation.

[1] Diane Leclerc and Brent Peterson, Back Side of the Cross: An Atonement Theology for the Abused and Abandoned (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2022), 39.

[2] Leclerc and Peterson, chap. 9.

[3] Leclerc and Peterson, 39.

[4] Keen Craig, “The Title of Pastor,” Social Media, Facebook, September 12, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/ArftheSquidKiller/posts/pfbid08bLT2zpZbpeUcSpqM4xLnL8126khACH7jBrmka8zXcdxAPWSswDgTy8sd9tWzcPyl.

[5] Priscilla Pope-Levison, Models of Evangelism (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2020), 150.

[6] Queen Latifah, U.N.I.T.Y, vol. Black Reign, 1993; Public Enemy, Fight The Power, 1990; Public Enemy, Fight The Power - Remix 2020, 1990.

[7] St. Athanasius Orthodox Academy, ed., The Orthodox Study Bible (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2008).

[8] Leclerc and Peterson, Back Side of the Cross, 51–55.

[9] Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson, eds., Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th ed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[10] Julian of Norwich, REVELATIONS OF DIVINE LOVE, ed. Warrack Grace (Digireads, 2013), 240.

[11] Leclerc and Peterson, Back Side of the Cross, 364.

[12] James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Reprint edition (ORBIS, 2011), 24.

Beautifully written once again, Brandon. Thank you for this insightful and life-giving approach to ministry in the 21st century.